Unlikely savages

The savage has been an image closely related to the history and representations of Latin America. This essay discusses varied artistic reinterpretations of the savage paradigm and the ideologies of domination and violence that support it. Though savagery seems to have changed forms, leaving the colonial world behind to reemerge as extreme violence often associated in Latin America with political questions, oppressive regimes, revolutionaries, and more recently drugs, the term is still deeply enmeshed with battles of dominion and representation involving many actors. The works analyzed address in either direct or veiled ways some of the convoluted relations between the so-called first and third worlds, alluding to everyday realities and imaginary ones through an extended notion of savagery.

The representation of Latin America as a savage haven has been a constant since its Western “discovery.” Even though it might be now amply recognized that the defense of civilization against savagery was accompanied by multiple acts of unabashed violence by its supposed evangelists and missionaries, it is still common to view and explain recent events and interventions in Latin America under the lens of some kind of natural tendency in its inhabitants towards savage behavior. Yet recent art production in Latin America has been involved in countering these notions while offering more complicated perspectives on the themes of violence, backwardness, and barbarism that impinge on the notion of savagery and its connection with a large, varied, and complicated continent. Some of these positions reveal the intertwined relationships between images produced for and from Latin America regarding its identity, as well as how stereotypes can be maintained in order to develop and justify specific discourses regarding violence and third-worldliness, and how the constructed notions of periphery and centers are enmeshed in mutual relationships of affirmation, negation, and power.

Though the trope of savagery is not intrinsic or particular to Latin America, it has a strong attachment to its history. From the first disoriented explorers passing through the colonial dispute of the indigenous possession of a soul or lack thereof, to the civilizing-evangelizing-modernizing mission of priests, entrepreneurs, and transnational enterprises alike, Latin America has been a fertile territory providing all sorts of beasts, monsters, and aberrations to be conquered, cleansed, described, surveyed, interpreted, and partnered with. As part of a dichotomy constructed by the West that opposes savagery to civilization and associates it with people without history or access to technology, as well as to the exotic, the primitive and the underdeveloped, the savage stood and still stands for alterity and otherness. The connection of this savage site to violence in the specific Latin American context has not only taken historically diverse forms that are a product of cultural misinterpretations (from the rampant cannibalism depicted in Theodor de Bry’s prints to explanations regarding a “natural” predisposition towards aggression sometimes justified through climatic theories, as in Alonso de Ercilla’s epic poem “la Araucana”), but has been another variation of the savage image that helped justify conquest, colonialism, and different kinds of more recent military interventions from abroad.

The image of the savage produced by Europe, whether by explorers, scientists, or ethnographers, has been worked in a persistent fashion since the 1970s by many contemporary artists and scholars from Latin America in order to question its validity. Many have literally taken prints, drawings, and paintings where those Latin American barbarians appear, studying the underlying stereotypes produced by them and their effects on the formation of an identity (as in several writings of Miguel Rojas Mix), juxtaposing their visages and tribal scenes to other forms of contemporary “primitivism” (for instance, in the art works of Eugenio Dittborn and José Alejandro Restrepo), and traveling to the remote wilderness to live among indigenous communities while attempting to unravel ethnographic presumptions through video (as in the case of Juan Downey). The graphic impulse to record the other that characterized for centuries much of the knowledge about so-called savage Latin American communities was reiterated through distorted copies that revealed other forms of violence (the violence of the gaze, of the colonial encounter, of the word and acts of naming, to name a few) different from the ones depicted in the images.

The video installations and related performances that the Chilean artist Manuela Viera-Gallo has been producing since 2009 in relation to the cannibal follow this path, while exploring the performative character of the savage image in the present. In a video installation titled “The Cannibal”, a large projection of a video by the same name shows a dark tunnel in what appears to be the middle of a park. The place seems to be inhabited by a strange naked, longhaired man whose main activity is to throw plates to the ground. In fits and spasmodic movements, the shadowy savage continuously takes ceramic white platters from a bag he carries and breaks them while passersby smoothly glide next to him, avoiding eye contact or any kind of proximity to his apparent rage. The distanced takes of this brutish body are interspersed with cuts that take an extremely subjective and corporeal approach, the camera being apparently manipulated by the savage himself, revealing his genitals and tiptoeing feet as he attempts to walk.

The high contrast of the image accentuates the shadowy underworld that this animalistic man inhabits, giving the video an expressionistic character that quotes the representations of the primitive from a European lens (as in the case of Die Brücke and other early twentieth century art movements). It emphasizes the obscurity to which the savage is reduced and from which he is believed to emerge, his darkness and opaque nakedness contrasting with the brilliance of the ceramic plates and the whiteness of the landscape beyond. While the plates may stand in for civilization, order, and manners, all of which the savage is believed to lack, they also allude to the work’s title in a frustrating manner. If this is a cannibal, then he is of the civilized kind, insofar as he does not ingest other humans but merely resorts to breaking plates in which they are served. Perhaps figuratively thus biting the hand that feeds him, the contemporary cannibal does not eat others, but unleashes his aggression in a much more contained manner. Such civility is reiterated in the avoidance and dismissal of those who pass next to the figure, as if he were just another ordinary sight of a naked madman in the contemporary world or, for that matter, an art project. Emerging from the earth’s vowels, or descending to a primordial cave, the savage seems to live right next to the civilized, or rather it inhabits its shadows as its unconscious.

The work has been installed several times with a variety of broken plates hanging in front of the video projection. Strung with heavy ropes and looking like lianas, the broken plates, glasses, and pieces of ceramic not only create a metaphoric forest (or jungle) of shadows, but turn the exhibition space into one of literal danger. The shards join the fragile and limpid materials with the violence that caused them to break in the first place, recreating a space of menace inside the supposedly safe institutional space of art. Similarly, the shadows they create obfuscate the video projection, interrupting the images and multiplying the shadows within it, denying viewers a clear “view” or apprehension of the subject. The savage is never clearly seen or encircled, just as the location of his “home” or the destination of his violence is not fully disclosed. In this way, the installation posits the existence of a third world in every first world (Minh-Ha 1987: 138) through shards and glimpses of apparently recognizable yet also absurd savage behavior. The primitive presented is only the acting out of stereotypes, cannibalism reduced to an ingestion and expulsion of myths and their never ending reiteration.

It is hard to think of art as a territory where savagery is an everyday affair rather than merely a represented one, yet a short story will help illuminate this question. A young Colombian artist doing odd jobs in London is almost miraculously contacted to do a job for a renowned compatriot artist in a famous British gallery. A little external research reveals that the artist in question is Doris Salcedo, a key figure in contemporary art narratives that have added a quota of Latin America conceptual art to their arcs, who has been known for her minimalist looking handcrafted furniture that reveal in their concrete additions, bumps, and scratched surfaces the interstices of a violent memory connected to her home country. The story goes that the young artist starts working doing absurd types of labors, because the well known artist had fallen behind schedule and had at the last minute decided to install in the large exhibition space fake walls with a metal grid imprinted on their surface. Because of problems encountered during the installation of the new walls, the well known artist decides to have her assistants fill the gaps formed between walls and unleveled floor, and then to cover their surfaces with glue in order to then sprinkle and dust off quicklime over them. Due to his naiveté and laid back attitude, the young artist soon gets in trouble, being ordered by the older artist to put his shirt back on when he took it off because of the heat, to stop chatting to friends who had accompanied the artist to install, and finally to switch the type of work he was doing, since the handling was considered to be unpolished and crude. In order to start the new task, the young artist has to move a ladder, forgetting that he had left on top of it a bucket of lime. The bucket falls; the powder spreads through the room and fills it up since fans had been placed in the room to bring down the heat. Chaos ensues: the older artist screams, damns, and curses the young, by then quite frightened young artist, ordering him to clean up with a vacuum cleaner. As he cleans, the cursing grows so insistent and malicious, that he decides to quit, leaving the vacuum cleaner on the floor, taking his things, and wishing good-luck to the older artist.

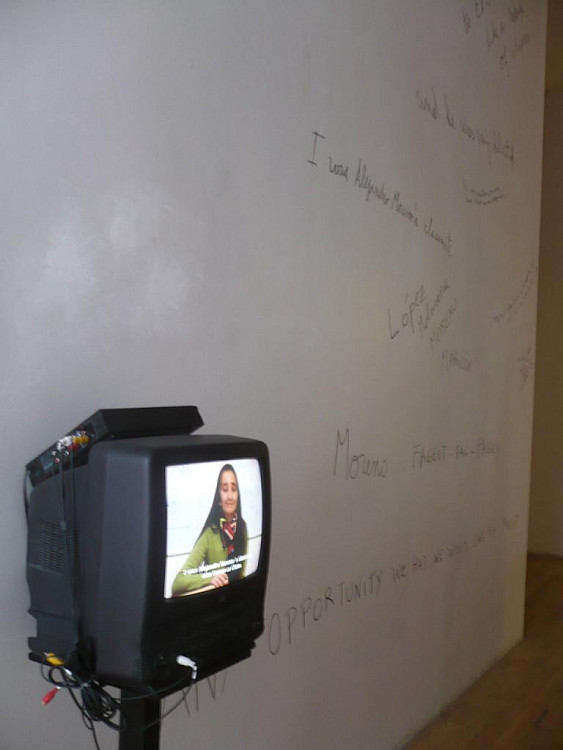

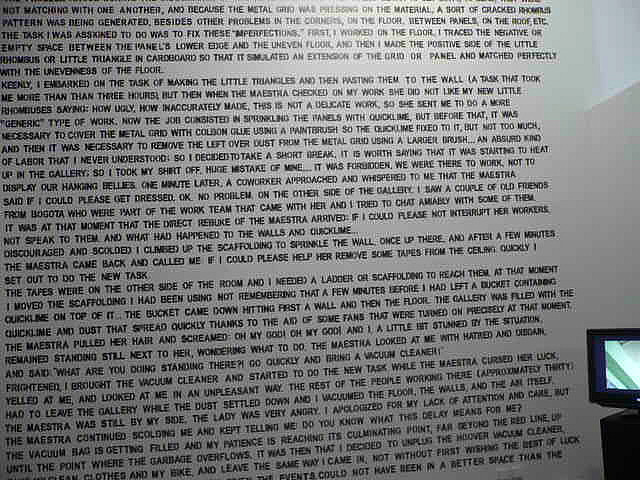

The narrative belongs to Colombian artist Elkin Calderón and has been told twice in the form of a large wall text that has either been scratched to a black-painted wall or written with black markers on a white one. Each time, the same old-fashioned letter mold has been used to stencil the letters composing the text. Helpers are hired and lowly paid to do the job, which usually takes more than four days with more than two persons working simultaneously. The dimensions of the wall text are dictated by the small plastic mold used to define the letters, though its orientation has changed from horizontal to vertical according to the proportions of the room it is shown in. Though from afar the wall text looks like a regular plotter, up close the letters reveal that they were handmade using a mold, showing signs of tiredness, energy, looping borders, change of hands, corrections, and badly calculated spacing between letters and words.

As the work reveals its labor-intensive production, it resonates with the story told within it. Using the first person, the story is narrated in a casual, loose, and ironical style that emphasizes the excitement of the young artist to see up close the work of a respected one, the surprise at the minute and strange tasks he is assigned to do, the servile attitude he has to adopt, and the bewilderment at the reactions that follow his laidback behavior and finally the overblown response to his absentmindedness (“Oh my god! Oh my God!”, “Do you know what this delay means for me?”). The humor in the text is nevertheless brought in tension with its own contents and its materialization in the present. In a performative turn (Austin 1975), the text enacts the forms of artistic exploitation it narrates by making those who actually write the narrative on the wall go through a similar experience of senselessness, strain, and toil. The work is based on the repetition of an act of bleeding another who needs the work (be it the curator and gallery assistants who are sometimes forced to write the text in order to make the work happen, the art students who want the experience, or the external help hired who could use a little more money) and the minimum traces it leaves of this assistance. What this reiteration attempts to make visible is a customary situation involved in the production of large-scale works by well known artists that nevertheless passes unnoticed in the finished work. It reveals a necessity and an abuse that gets naturalized and normalized through its very repetition and its current manifestation in the wall text. Though Calderón incorporates the names of the laborers next to the text as a form of retribution for their diligence, the laurels still go to the artist.

The work centers on two main issues: what makes artistic civilized behavior and the relationships of power that underlie the art world. The first concerns the behavior expected of artists in different social situations, the stereotypes surrounding them, and their actual actions. While the hyperventilating reaction of the older artist to the younger one’s mistake might be ascribed to some sort of artistic terribilitá associated with geniality and thus allowed to “star” artists, it also displays a despotism particular to individuals that is permitted within the art world. Even though that kind of tyranny regarding an artist’s own work, its fabrication and treatment might be related to perfectionism, intuition, passion, self-protection, and personal vision, in the case exposed by Calderón it is also related to whim, arbitrariness, and power. The view provided by the artist of the uneven power relations between employee and employees, fame and its requirements (that works be perfect, that they be grand, that the artist doesn’t lose her touch) is one behind the scenes, the attitudes that can be adopted when no one important enough is looking. If the closest that the art world gets to upfront barbarism is an auction that an interviewed auctioneer describes in Sarah Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World as “a real coliseum” and the author as a “gladiatorial spectacle” (Thornton, 5), what Calderón’s work exposes are the smaller beasts fed to the lions before the latter hit the arena.

Exploitation in other social fields has been brought to the center of art in the works of Santiago Sierra, well known for establishing uneven labor relations that put into focus the “antagonistic” relations in society in general and the microcosms of art in particular (Bishop 2004). In a similar manner, Calderón’s work focuses on the relationships between artists, curators, employees, and hosting institutions, testing their levels of resistance and acceptance of difference. He twists rather than merely invert or expose the relationships of power between players in the art field (from artist to curator to workers to gallery assistants), revealing the uneven position each occupies and their agency in replicating the system’s unspoken laws. The absurdity of artistic power is even reenacted in the act performed by viewers, who must go through the humorous yet tiring motion of reading the extremely long text in order to finish “seeing” the work.

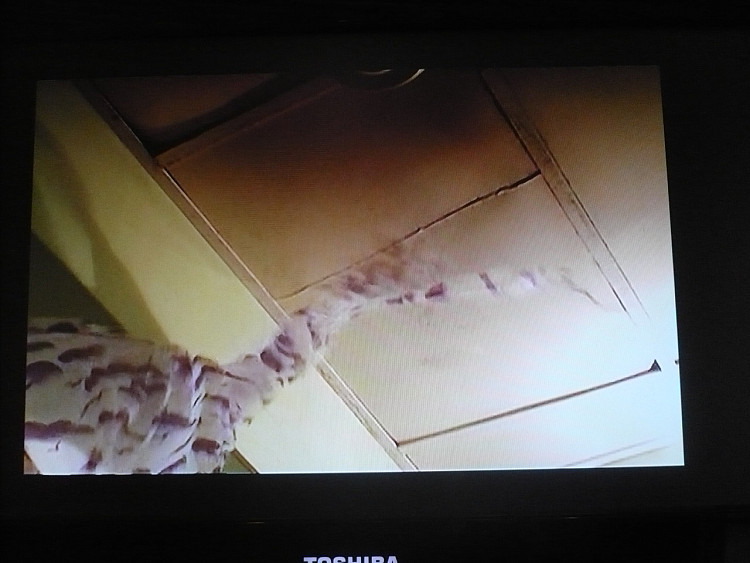

Counterbalancing the massiveness of the text and its labor is a short video titled “Ventiladoris y serendipias” (2010). Usually shown in small screen right next to the wall, the video begins with a slow continuous shot taken from the bed of a cheap hotel room. As the camera moves upwards from bed it focuses on a free floating white curtain separating two rooms. Apparently old, since its edges are shredded to pieces, the curtain has cloud designs stamped in purple, suggesting a balmy ambience and breeziness that is repeated in the subtle arbitrary movements that the thin curtain actually makes. As the camera follows the waving movements of the torn curtain, taking delight in its flights and tossing, and moves slowly towards the ceiling, an electric turned on fan is revealed as the origin of the “breeze”. Yet a few more seconds pass before what first seemed like a celebration of the poetics of everyday life and humble surroundings changes entirely. For the fan not only initiates the curtain’s tenuous gestures but, as the video soon reveals, it is also the weapon that when in sudden contact with the waving curtain, rapidly cuts and severs it. The unexpected violence of this quick and evidently repetitive interaction (due to the proximity of the doorway where the curtain is located and the fan, the latter cuts through the curtain each time it is turned on) is reinforced by similitude between the sound that this contact makes and a firing machine gun. A violence that is then forgotten, since the curtain moves downwards in order to recommence an upwards flight once again. Though finding the unexpected, the marvelous, in the quotidian was a characteristically Surrealist concept and method, when linked to spaces of armed conflict such sur-reality becomes even more disturbing. The “naturalization” and everydayness of violence seems to be just as artificial as the purple palm trees imprinted on the white fabric, or perhaps such aggression is just another component of the exotic other.

Violence and barbarity can thus be found in the most unlikely places. The location of violence, the spaces and places where it appears and exerts itself, is just as relevant as the bodies and objects it forces itself on. The art world has all sorts of levels where violence is acceptable, such as representations, performative enactments, and even work relations (biting off heads in editorials is just one civilized way of engaging in intellectual duels), as long as it is kept within some kind of limits or behind closed doors. Savagery is also a spatialized phenomenon, at times geographically delimited, at others institutionally demarcated. In his work on prisons and historical forms of punishment, Michel Foucault has analyzed the importance of the spatiality of violence and control in the production and dissemination of discipline and power, linking different disciplinary institutions and apparatuses with similar methodologies of supervision and spatial layouts (Foucault 1977). Interestingly, though the Panopticon model has gathered most attention, the school offers a particular location where savagery emerges and violence is applied from the top down as well as from the bottom up. Even though “justified” physical violence was pedagogical norm for centuries and has fallen in disuse and criticism, psychological trauma has only recently been attended to as another form of educational aggressiveness, especially through the recent interest in bullying (from president Barack Obama to Ellen DeGeneres).

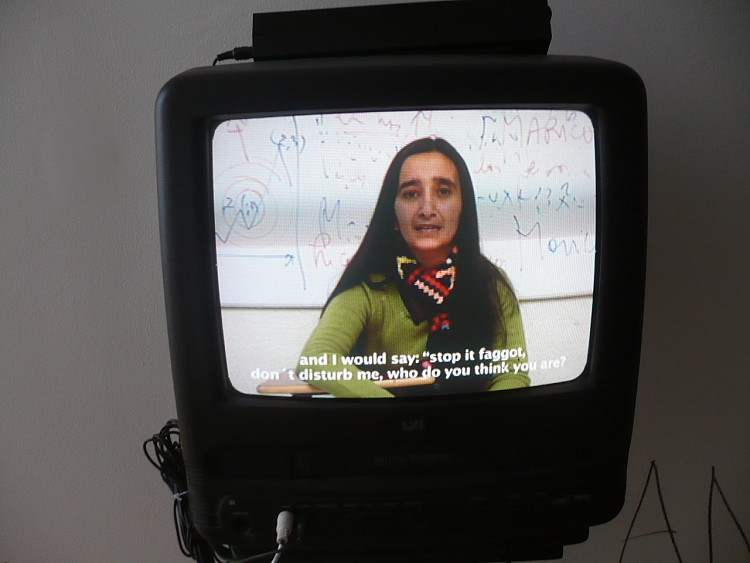

Children can be little beasts, savages of the best and worst kind. In their innocence and mixture of honesty and maliciousness they can apply a particular kind of brutality to their peers that might be left behind as they grow up or endure within them and resurface under the most unlikely circumstances. Such is the case exposed in Alejandro Moreno’s video “La Chata” (2010), where the classroom becomes a torture chamber that both victim and aggressor revisit in an apparently civilized manner. The video takes place within a classroom of what apparently was the school in the desert northern zone of Chile that both the artist and his friend attended and where they reunite years later to talk about the past. Through a series of shots with a still camera that centers the subject of speech in the image, rendering her apparently objective though evidently uncomfortable in the too small school chair, there is a slow unveiling of stories that begin in a passive, friendly manner, until hate and discrimination begin to surface. As the woman is left to talk and reminisce, her own fears and hateful feelings towards her old friend begin to emerge under the apparent caring words that she manages to intersperse into the horrendous stories of bullying she so casually narrates. These revolve around the artist’s homosexuality and gender and the ways in which these Chilean children dealt with prejudice, difference, and their own ambivalent feelings. Though their jokes could seem at first merely children’s games, such as the distortion of the name and nickname of the artist by re-gendering it female (from “el Chato” to “la Chata”, which gives the video its title), they rapidly escalate to more abusive phrases, games, and actions that continuously and in an almost ritual manner reveal the crude violence of sexual stereotypes. Closely bound to their “finis terra” Chilean context, and further locked in a provincial town within it, the children’s words that are reenacted through their grown up version reiterate a series of stigmas marked by an intolerance that forms part of Chilean idiosyncrasy. Savagery is also present in the heterosexual model passed on through education, hammered in school relations, sanctified through Catholicism and even politics (not very long before finishing this text, Chilean president Sebastián Piñera announced that marriage should be between man and woman only).

An interesting fact of the video is that the insider-friend who tells the story still laughs at the jokes and seems to show very little remorse or questioning regarding their childish actions and the impact they may have had on their “friend”. The stillness of the camera, the image’s plainness, and the tight space in which the woman sits not only creates a prison-like ambience of boiling pressure but also emphasizes the tics, nervousness, and hysterical laughs of the narrator, who seems caged. When she finally reveals that after a while of not knowing where her friend was, she got news that he had become an important playwright, and as the viewer realizes that the woman remains tied to that small provincial world, unable to surpass her prejudice, she becomes an unwitting witness to her own bigotry. I would call it artistic revenge, another kind of violence.

The visualization of violence is another arena where savagery takes center stage. A large part of the savage paradigm consists in its capability of being imagined, recognized, represented, and thus reproduced. As Franz Fanon argued regarding otherness, feelings of inferiority, stereotypes, and discrimination, the visible marks of the other are needed to install systems of difference and racism: appearances determine and act as visual “evidence” of otherness (Fanon 1967: 117). But these marks are not merely imposed or fantasized; they are created from within and without. While savagery gets constructed from the outside through an evaluation of actions and behaviors that are opposed to others valued as superior, it can also be said that savagery creates its own cultural forms, as well as ways of seeing and doing, in short, a sensibility or aesthetics. Though violence may get stereotyped and even aestheticized from the outside, savagery creates its own language and way of being in the world, adopting different attitudes, poses, masks, and all sorts of accruements that signify its force and distinguish it from other kinds of violence. Some chop up bodies, others hang or crucify them, creating specific spectacles and developing particular techniques and technologies to do so. The savage breeds a cultural realm, shaping behaviors and thoughts, transforming culture. Yet both sides depend on the visual realm for their efficacy, manifested in their ability to make an appearance and be apparent, to occupy and be seen on a stage. Savagery, and its correlative of violence, is exhibitionist even when it negates its own spectacle.

Yet images do not circulate in the same manner and stages are not equally lighted. The visualization of savagery is based on the circuits where images move, as well as what gets to circulate in certain spaces and what gets excluded from them. Embedded in interconnected systems of power, these visual platforms conduct their own discriminations based on looks. It is by now no surprise that some forms of violence get excused and quietly effaced or disguised and applauded, while others are openly abhorred and punished with more violence (instead of tomatoes thrown at the performers, bombs are dropped). What can be surprising are the visual forms that violence and savagery take bypassing at times their common outlets and stereotypes, as well as the stages they generate to be seen.

An example of an alternative theater of violence is the one disclosed in the video works and related drawings of Colombian artist Wilson Díaz. “Rebeldes del Sur” (Rebels of the South) of 2002 is a video that documents a particular stage that was set up in a strange no-man’s land in Colombia in 2000. The video was recorded at the “zona de distención” (distension zone) created by then Colombian president Andrés Pastrana, a neutral, demilitarized territory of more than 42 thousand square feet in the south of the country. Creating a space within space where the normal state laws did not apply in order to meet and conduct peace talks with the FARC guerrillas (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) and their leader, Manuel Marulanda Vélez, for a little more than three years starting in 1998 a new geography of power was implanted in San Vicente del Caguán. Beyond the territorial conflict of domain, sovereignty, and constitutional rights that the creation of the distension zone and its application by the State implied, as well as the changes it supposed for the zone’s inhabitants, Díaz centers on the semi-public media space that was created in parallel, the problem of visibility of this internal war, and its diffusion. For this no-man’s-land was not only a space of negotiation and mediation, but a place where to showcase the conflict between government and guerrillas, along with their demands and ways of interpreting their problems.

A period of public “audiences” was established to discuss within the distension zone the concerns of the involved parties. During these series of public meetings, the media was invited to attend along with artists and cultural producers. Entertainment and cultural shows were mounted for these concrete audiences, several of which were recorded in a precarious manner by Díaz, forming the basis of “Rebeldes del Sur.” In the video, through the slightly jittery movements of a hand held camera, different performances set on two stages within an enclosed space and under a tent were filmed by the artist, particularly musical performances. Dressed in their combat outfits and sometimes holding rifles, FARC members sang, danced, and played instruments to the rhythms of “vallenato,” a popular musical genre form the northern coastal regions of Colombia. The lyrics remained at times similar to those of regular vallenatos, dealing with love subjects and woes, while at other times their content changed to reveal the guerrillas’ political and armed struggle, the poverty surrounding them, the massacres conducted by the government and paramilitaries, and the social problems that justified their fight. In the video, culture became a site of struggle, with violence fueling its forms.

Though the artist assumed a traditional ethnographical eye/I by going to the place where this particular nomadic community temporarily resided and observing the group’s behavior and their interactions with others (the media and cultural agents that had come to participate in the talks or watch), what was being recorded was more than a “natural” behavior, but a show prepared for “others” who had been invited to observe them. The distension zone was also a platform where the visibility of the group and its preoccupations was under scrutiny. It is interesting and contradictory in this sense that the outfits with which most of the FARC members performed were their camouflaged uniforms: while in an everyday context they are used to hide the guerrillas from the unwanted vigilance of the state or paramilitaries, making them “invisible” to certain types of gazes and providing them with a hideout, the uniforms became in this particular platform visual signs of their struggle and clandestine way of life. A tension was thus created between being seen and disappearing from public view, making public statements through popular forms of music, and projecting an identity as a group. The video questioned how armed groups are represented by the State, the media, popular culture and how these representations contrast or join the images that the guerrillas produce of themselves, focusing on how violence is visualized and transformed into particular spectacles.

Inadvertently, the video also exposed the circuits in which such spectacles are allowed to be reproduced. When the work was shown in the exhibition “Displaced” at the Glynn Vivian Art gallery of London in 2007, the video was physically removed by the Colombian cultural aggregate by orders of the ambassador, who then claimed that this was no act of censorship (Villamil 2007). Curiously, though in the video Díaz’ camera often turns to the public gathered round the stage evidencing the presence of more cameras and even of the National Institute of Radio and Television INRAVISION, few images regarding these performances have reached the public. This lack of visibility raises a double question: on one hand, which persons are authorized to represent the different sides of armed conflict, what images are allowed to circulate and how, and on the other, it posits a question regarding the intentions of the video as document. In other words, the video is connected to the problem posited by Ingrid Johanna Bolívar and Alberto Florez who, in relation to violence and its conceptualization, have asked whether the researcher “may suffer from some sort of “Stockholm Syndrome” by living with the informants until they are recognized as so human that their violent behaviors are minimized? Where does the camera point to?” (Bolívar and Florez: 39, my translation). Does Díaz humanize so much his subjects by showing them as sentient human beings who also play music and translate into “vallenato” lyrics their preoccupations that it is difficult to balance this with the weapons they hold and what they suggest? Was he, as argued by the Colombian authorities, distorting the facts and “promoting” the actions of a “group outside of the law”? Several articles have exposed how this act of censorship has negated the conflicting and not so beautiful realities of the country. As Colombian politicians and enterprises attempt to cleanse the nation’s public image (as exemplified by Avianca airlines advertisement shown on their airplanes: “the only danger is that you want to stay”), the relationships between politics, armed conflict, paramilitaries, and drugs are camouflaged as well, reducing the social problems behind the armed conflict to a discrete problem of internal “terrorism” (Guerrero 2007). How this conflict is being solved, the violence embedded in “Plan Colombia” (a U.S.A supported program), and the continuing acts of savagery performed by all involved sides points to the complicated and entangled roles of those involved in the drug and guerilla conflict.

Today, the drug conflict makes up one of the important and thorny subjects concerning international relations and the image of savagery that Latin America projects to the world. Drug traffic forms another set of corridors and interconnected routes in the globalized world, joining and dividing nations, economies, politics, fields of production, and forms of violence. The war on drugs is just one side of a civilized war waged against a form of consumption that has an international market fueled by all sorts of needs: from lack of employment and means of subsistence by impoverished, marginalized, and violated populations, a form of financing other violent activities (as in the case of guerrillas, paramilitary or self-defense groups, and political campaigns), desire for power and territorial control, addiction, to entertainment and more. Though Colombia is notorious for the twisted connections between drugs, politics, territorial conflicts, and violence, Peru also shines on this stage with its own bright light. Among the first twenty drug producing nations worldwide (UNODC 2010), Peru has a long historical relationship with the cultivation of coke plants in particular, ranging from medicinal to ritual uses. Yet its importance today in the political arena, both in the visible realm of policy making and armed struggle as well as the apparently invisible site of personal use and political campaigns and support, has acquired a new urgency as has been recently manifested in a series of articles have appeared in the Peruvian press linking congress members with illegal drug traffic (El Comercio 2011).

These tangled webs are given an imaginary ambience in the video “The Act” (2011) by Peruvian artist Diego Lama. Through a series of apparently documentary images of an empty Peruvian congress and the eruption of oneiric events within it, Lama explores the architecture of power influencing the construction of a savage Latin America. To the accompanying music of Claude Debussy’s “Clair de lune”, a series of tranquil and fading shots of the main room of the Peruvian congress are interspersed with details of its decorations, such as the white and gold neo-baroque ceiling, the patriotic bronze reliefs displaying battles and heroes, and the velvety red carpeting and wooden upholstery. Views from the front, sides, and back of the room emphasize through the symmetrical repetition of rows its sense of order, peace, and dignity, while the rising melancholic notes from the piano in Debussy’s well known work tinge the whole with an aura of nostalgia. Such a romantic ambience is reinforced by the strange white particles that seem to be floating in the air, shown in individual shots as some kind of misty atmosphere that slowly invades the space and falls gently on the carpet like snowflakes. Because their origin is uncertain, the particles appear as somehow part of the site, contributing to the hazy atmosphere created by the music.

The strangeness of the whole scene is exacerbated when the continuity of the music stops and is punctuated by a series of four arpeggios, which are then followed by a more active and fluid last part. The clusters of notes coincide with the sudden downpour of four streams of white dust in the curved area in front of the speaker’s podium, offering a comic relief that continues as both music and powder begin to flow rapidly. Like divine semen falling miraculously in a shower from the open sky, the white powder accumulates in a small mountain at the center of parliament, a pyramidal pile of bright dust ready to be adored or literally inspired. Such magic is nevertheless broken by the connection established between the territory of the law, common good, and representation, and cocaine.

The theatricality of parliament and its impossible mission to represent the people are suddenly exposed through the intervention of the apparently mysterious and even fateful powder. Through the digital appearance of the white dust, “The Act” seems to point to the behind the scenes of parliament, what remains hidden in the side wings yet blasts the gravity of the space with its ejaculatory suddenness. The overriding yet fuzzy presence of drugs in the midst of this legal institution and its violent discharge directly inscribes this site and its absent members with illegality and possible violence. If, as Walter Benjamin once described, the acts of parliament are violent insofar as lawmaking is an active form of power, the power associated with drugs brings about a whole new culture of savagery. Even though the video’s indictment is directed to Peruvian politics, drugs have become the white elephant in the room in international relations when discussing Latin America and, for example, free trade agreements, military cooperation, questions of security, health, and violence. Though the drug conflict is multi-sided and involves many actors and nations, it often gets reduced by governments to a problem of illegal production and gang-related power struggles confined to particular locations (the “cartels” for example) that can be countered with more violence (as in Plan Colombia), diminishing the questions of poverty, social injustice, and drug consumption that also form part of the problem. What interests are indeed represented in parliament is a question left hovering by Lama’s video along the white dust.

Representation is not only linked to identity in the form of internal and external projections of a self, but is also tied to forms and technologies of viewing. Information regarding the other is transmitted through a wide range of visualization technologies that allow for particular readings or understandings of the image produced. Though the medium is not entirely the message as Marshall McLuhan would have it, the material transformations of particular mediums and inventions are joined to ideological mutations concerning its contents and effects, altering our own perception of them. Though the savage trope seems to be immutable and resistant to passing time, it nevertheless has significantly altered forms and even meaning in each appearance it has made. While it may seem obvious that a seventeenth century print of an indigenous Latin American man made by a European traveler as a composite of men and ethnic characteristics is far from the documentary films of twentieth century anthropologists living with their subjects of observation, the technologies of viewing that support such images (such as translating personal visual information into a series of traces made by hand that will then be reworked on a metal plate to be reproduced in books and individual plates versus hiding the eye or supplanting it for the camera lens which will electronically or now digitally transmit electric signals or data to a recorder) help create contexts and processes of identification (or mis-identification) with those images.

Visualization forms part of the title of a series of video works by Nicaraguan artist Ernesto Salmerón that take up the spectacle made of Latin America and its supposed savage behavior, particularly through the form of revolution. If there is one myth or image that has accompanied the Latin American savage in the twentieth century (though its roots can be found a long way back in the colonies and the fear surrounding the other), it is that of revolution. Conjuring up images of popular revolt, brutal death, and peasants along with long haired intellectuals bearing guns, revolution forms part of a history of decolonization and class struggles in the Americas whose varying forms of visualization have produced radically different ways of interpreting these events. Though Salmerón has been consistently working in thinking about revolution today and the changing meaning of popular fights in connection with the Nicaraguan context and the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), in the series of “visualizations” he explores the relations between different technologies and spaces of viewing and the images they help project, attempting to undo or reinvent forms of looking, screening, and agency.

The videos forms part of the work Salmerón has been producing in a small city three hours north of Managua called Jinotega, where he has established an artist residency of sorts. Under the title of “Taller Imagen Tiempo” (Image Time Workshop), the artist has been expanding a project that is a never-ending archive formed out of literal bits and pieces of other film and found footage belonging to disparate visual annals around the world. Assembling these pieces together in altering combinations and montages that can then be filmed, photographically documented, videotaped and played back, projected onto multiple screens and settings (from hanging bed sheets to the sides of trucks, as in Jinotega), and taking each act of viewing as another link or data added into the collection, Salmerón performs an arch-archive, a record with no beginning or end, expandable and condensable. More than a work-in-progress, this is a work-in-mutation, a work that never coalesces in just one thing or product, but which branches out in multiple variations. Its own networked aspect reflects the networks of power, communities, and conflicts that both dilute and form revolutions and wars, elements that can be seen as active or reactionary, passive and aggressive.

“Acción de visionaje 001” (Visioning Action 001) is a short video that begins with the excited expectation created by the cinematic countdown. After locating the viewer at another time frame through this quote to a film screening device, a schematic map of Central America that highlights and focuses on Managua, Nicaragua, locates the viewer geographically. The appearance of all the material seems to be derived from 16mm film, particularly as the blinking images seem at times to be projected onto different surfaces. A series of rapid cuts follows this introduction showing soldiers, black leaders from other countries doing speeches, handicraft work, views of passersby in a modern looking Latin American capital still bearing traces of its colonial past, references to napalm, religious figurines and comic book superheroes on displays, different forms of play by children and adults, and a movie kiss, reaching an apparent end or new beginning when the encircled numbers of the film’s countdown appear once again. The reiteration is nevertheless followed by variation: images of crowds applauding, bucolic landscapes, as well as references to industry and different kinds of labor, from trucks to work done in the fields by indigenous peasants. The video ends abruptly with a screen within the screen, as the images seen are revealed to have been seen through a small television display.

The vision alluded to in the title is constantly being interrupted by the video’s flickering rhythm. The continuity of the sequences is broken by the film projector’s blinking light, the separation of the frames, and the montage that exacerbates the concrete cuts in the film, creating a series of flashing images. It is only through glimpses that the viewer observes multiple and discordant histories woven and patched up together. The video negates the possibility of forming one big picture or having a totalizing view of a subject that seems to split into many, or of one territory that nevertheless is shown to have myriad relations to other places and appears to be in constant change. While some of the images come from Latin American archives and newsreels, others for example come from the United States government and its educational programs on Latin American countries produced during the 1940s, reinforcing the sense of interconnectivity, the lasting effects of imperialism, and the ways of looking and presenting a “view” of the remote and savage place.

The passages between mediums and the hybridity of the whole product are also emphasized, re-presenting the ambiguity of the archive, the memory it supposedly preserves, and the acts of vision that make it actual. From photography to cinema, passing on to video and the internet, where the video itself can be seen (at vimeo), these diverse technologies of vision and documentation associated with the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and moving from the material to the virtual, are not only brought together to reveal different ways of looking at and projecting an image of Latin America, but are re-projected onto multiple surfaces: streets, trucks, walls interior and exterior, virtual and concrete screens. The video itself is a document of a series of interventions onto social skins/screens as it displaces the interior or private screening of film to public spaces, creating new stages for viewing. Furthermore, the work does not merely bring all the documentary fragments into life by rearranging them, but gives an account of their discourses and other lives by activating them, making the images act and interact with concrete spaces, such as the streets of Jinotega, and the very objects of vision who now act as spectators to their own images. At times, by being captured watching the screenings, the observers also end up in the picture, as Lacanian stains. In a way, the video is a “performance of vision itself” (Bodenhorst 2005), as it stages different forms of looking, re/enacts diverse gazing positions, and makes of current spectators simultaneous objects of vision and observers.

The video also places a great emphasis on the screen as a site of projections. These come from both past and present, inside and outside, and merge different temporalities by means of the multiple screenings that the images go through. While the past is projected onto the present, the present seems to illuminate the past, shedding light on the convoluted relations between nations and their cultural memories. On one hand, stereotypes abound and Latin America appears as one big fragmented spectacle in the documentary images that connect poverty with victimhood, as well as the contrast created between modernity and cultural backwardness and the latter’s overcoming impersonated by the Indians working at factories. By cutting through the images and narrations, the video focuses on the production of images concerning the other, putting in tension the idealized representations of the idyllic countryside and the misrepresentation of Latin American nations as placidly developing places. On the other hand, the ambivalent love affair of the United States of America in particular with its southern neighbors is reinforced by the passionate on screen kiss that suddenly disrupts the apparently documentary character of the other visual sources, reminding the viewer of the artificial and fictional character of the images being projected as well as their rootedness in popular culture.

The last aspect of the video which more closely connects its images to the trope of revolution is the soundtrack. The images are synchronized to the song “Llégale a mi guarida” from the Cuban group Calle 13, a song in which the Argentinean singer Vicentico (from Los Fabulosos Cadillacs) collaborates. The song is dedicated to Nicaragua as can be told by the direct references to its landscape (such as the volcano Masaya) and its politics (as in the mentions to the Sandinista fight), yet it consistently connects revolutions in Latin America to those of other nations and groups. It also plays with stereotypes related to savagery and violence (“quickly I turn brute like a caveman”), specially attacking foreign intervention in domestic affairs, yet turns these images into an indictment of unbridled hate toward any kind of otherness. Salmerón’s video plays with the culture industry and popular culture from all sorts and fronts, by making his own work resemble the montages and discontinuities of a music video, while renouncing to coalesce in a clear message. It presents fragmented forms that recreate the processes of construction and reconstruction of both Nicaragua and the image of Latin America while reminding viewers of their own agency in the act of gazing and reconstructing history from its archival remains.

A last related aspect concerning the savage trope and its visualization, involves its relationship with technology. Lack of technological advancement has been one of the main parameters to judge degrees of primitiveness and savagery in colonial and older anthropological discourses, placing peoples entirely out of history and the later discourse of development that took sway in the twentieth century. Though this situation has changed through a critique of the discipline and its ethnocentric biases starting in the 1980s, several recent studies (Escobar 1999) have shown that globalization and technological penetration in the world at large has changed the ways in which the savage paradigm is understood and studied. Though lack of access to technology is still an important matter for a greater part of marginal communities and so called “Third World” populations, it has also opened new possibilities of imagining the savage.

Such a position is taken up by Colombian artist Andrés Burbano, who has explored the relationships between technology, translation processes, and representations of the primitive. In the video that forms part of the project “Open-ing-Source,” Burbano presents an actual experience of cultural shock and translation in the remoteness of the Colombian Atlantic coast. The artist takes on the role of anthropologist and ecstatic colonizer who, while visiting the coastal region of La Guajira, records the pristine solitary landscape. The video exacerbates the sensation of marvel felt by the artist in front of such raw and stunning terrain by presenting accelerated images of the artist’s run with his camera along the beach as he filmed the deep turquoise waters. Subtitled to explain the location and the way of life of its predominant indigenous nomadic population (the Wayuu), the video seems like an amateur anthropological document. Yet the narrative changes when the artist sees “far far away” a “ranchería,” a small precarious construction and approaches it in order to discover a child in a hammock. The stereotypes of the other are confirmed through this finding of such a rudimentary home and the symbol of the primitive incarnated in childhood and its innocence. A conversation ensues between the two, accelerated as well, until the video regains a normal viewing pace and a fragment of the talk can be heard. In his amazement at finding the child in the midst of nowhere, and while holding his technological weapon in one hand, the artist asks the boy what word is used in his own language for “technology.” The artist’s surprise is evident when he hears the answer: “ROBOT!” and as he dubiously reiterates the word so as to confirm such exotic and international vocabulary within such a precarious setting. The video ends with a text explaining that the word robot has a Czech origin in science fiction, pointing to the unimagined ways in which technological languages travel and mutate.

The video posits the question of how languages and practices related to technological changes experienced in the last centuries affect and transform ways of life and identities. For not only is his own identity as the video-artist/anthropologist questioned by the child’s happy response (as in “are you nuts? It’s robot, silly, didn’t you know?”), challenging the preconceived image he (and we as viewers) carry regarding otherness, but the identity of the Wayuu is also revealed to be more complicated and globalized than what is assumed. The video thus signals how technologies and cultures alter, questioning how certain discourses regarding primitiveness and savagery are preserved from one side and the other. As the subject of technology and vision is destabilized in his apparent mastery of language and knowledge, the object of study becomes an active agent that appropriates the language of his “other,” reinvesting it with meaning. If the introduction of European technology was a necessary evil for the conquest and “civilization” of cultures considered “primitive” in the Americas (and around the world), Burbano’s video shows that not only does this technological penetration occur in multiple levels and in continuing processes, but it signals the possibilities of appropriation of technology and its language by the apparently “primitive.”

Burbano’s video leaves an open question regarding the present and future relations between technology, power, minorities, and dominant cultures in an interconnected world. It posits an unlikely form of savagery that unsettles dominant discourses regarding Latin America and its development. Several young artists have embarked in a process of questioning terms like “development,” “civilization,” “technology,” and their opposite embodied in the “savage” as interpretative frames regarding otherness, asking how these discourses have helped shape the identities and projected images of different populations in Latin America, as well as how these concepts have changed. They also point to how we may envision news forms of alterity, hybrid and mutating ways being, as well as the varied realities that exist today in a globalized landscape, while recognizing the disparities and prejudice that still taints intercultural relations. They speak of how difference is constantly being performed and negotiated through images, technologies, and acts, and the challenges we confront when thinking about contemporary forms of savagery and their own mutations.

Bibliography

Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1975.

Benjamin, Walter. “Critique of Violence,” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, trans. Peter Demetz and Edmund Jephcott. New York: Schoken Books, 1969, 277-300.

Bishop, Claire. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall, 2004): 51-79.

Bodenhorst, Cynthia. “The Underskin of the Screen: Performing Embodiment Through the Looking Glass, an Installation by Cris Bierrenbach,” emisférica 2.2 (Fall 2005), accessed May 29, 2011, http://hemi.nyu.edu/journal/2_2/bodenhorst.html.

Bolívar, Ingrid Johanna and Alberto Florez. “La investigación sobre la violencia: categorías, preguntas y tipo de conocimiento,” Revista de Estudios Sociales 17 (Feb., 2004): 32-41.

Burbano, Andrés. “Traducción [ex machina],” Cuadernos grises 2, issue on Arte y traducción (July, 2006): 61-87.

Díaz, Wilson. “Rajaleñas,” in La casa por el aire [Taller Juanchaco, Ladrilleros y La Barra]. Cali, Colombia: Helena Producciones, 2010, 63-65.

Escobar, Arturo. El final del salvaje. Naturaleza, cultura y política en la antropología contemporánea. Bogotá: CEREC, 1999.

Fanon, Franz. Black Skin White Masks. New York: Grove Press, 1967.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage, 1977.

Grenfell, Damian and Paul James, eds. Rethinking Insecurity, War and Violence. Beyond savage globalization? New York and Oxford: Routledge, 2009.

Guerrero, Diego. “Dos videos sobre Farc fueron retirados de exposición en Inglaterra por embajador colombiano,” in esfera pública, Accessed May 29, 2011,

http://esferapublica.org/portal/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=386&Itemid=1.

Lawrence, Bruce B. and Aisha Karim, eds. On Violence. A Reader. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw Hill, 1964.

Minh-Ha, Trinh T. “Of Other Peoples: Beyond the “Salvage” Paradigm,” in Discussions in Contemporary Culture, ed. Hal Foster. New York: The New Press, 1990, 138-141.

Thornton, Sarah. Seven Days in the Art World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008.

Trend, David. The Myth of Media Violence. A Critical Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

UNODC. “Monitoreo del Cultivo de Coca en el Peru, 2009,” in United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2010, accessed May 29, 2011,

http://www.unodc.org/peruandecuador/es/areas/monitoreo/informe2010.html.

Villamil, Ivonne Viviana. “Pareciera que nadie quiere victimarios,” in esfera pública, http://esferapublica.org/portal/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=386&Itemid=1. Accessed May 29, 2011.

“Congreso no profundizó investigación a Obregón por vínculos con el narcotráfico,” El Comercio, May 10, 2011, accessed May 28, 2011, http://elcomercio.pe/politica/755193/noticia-congreso-no-profundizo-inv….