Tehran is a city of contradictions, contradictions that have come down the path of history from yesterday to tomorrow together with the city and its people. Whenever they go beyond the city and people’s capacity, they stand out and if not, sleep within the gigantic city. Tehran is the city of weird symbols. Everything in it has the potential of turning into a symbol or contradiction. In Tehran, huge buildings rise next to tiny brick and mortar houses. A balloon becomes the symbol of anarchy, colours are limited and Azadi Cinema burns down so as to be replaced a decade later by another Azadi, five times bigger. Life in Tehran has had close ties with contradictions since long ago.

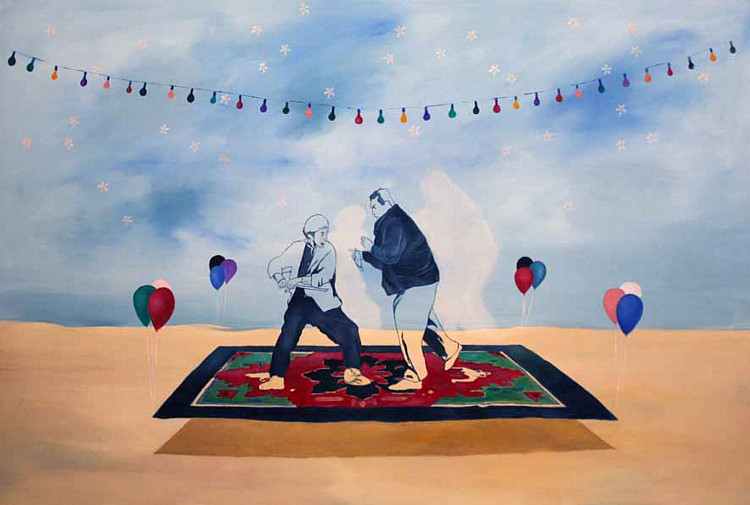

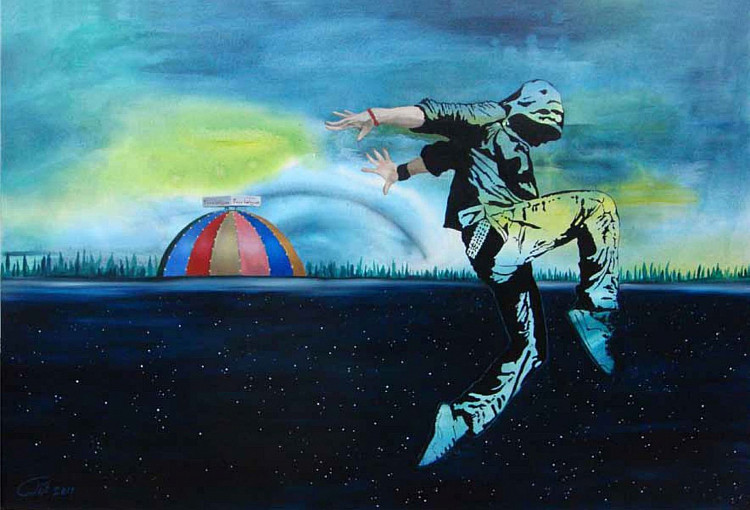

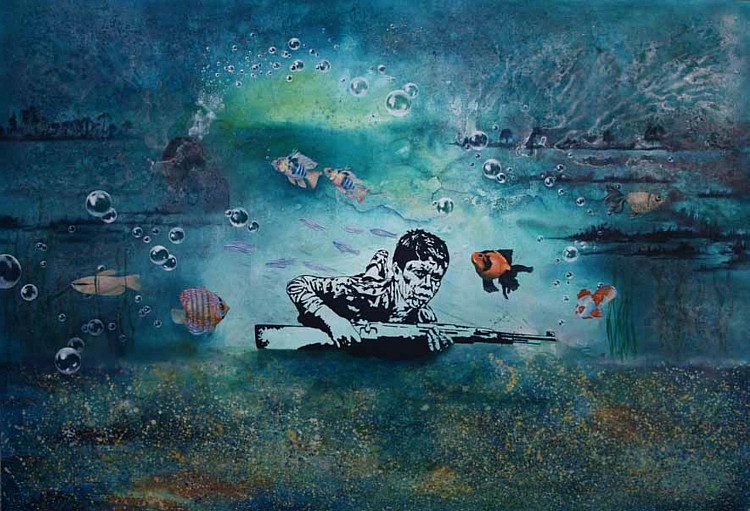

A Canada Dry advertisement on a billboard reads, ‘Welcome to Tehran!’ The style takes us back to years ago, to Tehran in the 50s. On the right hand side of the billboard there is a famous picture of American athletes (Tommy Smith and John Carlos) who held up their black covered fists in protests when awarded their medals turning into eternal historical figures. This is the first work in Mohammad Eskandari’s Heroic Tehran series providing the viewer with the main characteristics of this series of works; a combination of contradictory visual signs which in the first glance seem irrelevant. Contradiction and irrelevance are the main elements of Mohammad Eskandari’s visual society. Signs are apparently contradictory yet this contradiction creates parts of notions and narratives towards which the artists want to divert viewer’s attention. In most of the works, we see a series of signs signifying a particular site. Next to them, other elements referring to time, speak of yesterday, today and tomorrow; of yesterday’s regret, tomorrow’s hopes and a nostalgic oscillation between the two which is today. Some motifs in this series contradict their essence, such as the decorated Tiananmen tanks. Other contradictions are found between men and objects, such as a soldier looking at and holding lovingly to a dust mop. Elsewhere, an opposition between the uncertain and doubtful ‘situation’ of men and the stability of contexts is rendered questionable and contradictory. Eskandari’s figures are in an unstable situation and call to mind a transitional moment whose result is not clear. Will they reach stability or will they fall to the ground? This might apply to many of us and many of people of our time, such as the figures dancing in front of a 50 Toman banknote.

Through using nearly monochrome atmospheres, in the visual structure of his works Eskandari creates an obscure and foggy perspec-tive imbuing time and place with a mysterious quality which conveys that what is seen is not all of the reality. Another important fact is the shape of figures represented in a visible and invisible form, like silhouettes whose existence is hidden in an ambiguity. He consciously insists on using, however in a more precise and detailed manner, the visual style of graffiti artists such as Banksy who have become a symbol of modern urban anarchism.

The sum of these contradictions is Mohammad Eskandari’s descriptions as well as his clever, lyrical and emotional copying of the Zeitgeist of a city in which he lives guiding the viewer to a lyricism mixed with regret and irony.

We

Are the conquerors of lost cities,

We narrate forgotten stories,

With a voice that is too weak to come out of our chests.

(1968 Olympics Black Power Salute - Akhavan Sales, End of Shahnameh)

text by Behrang Samadzadegan